[1] Net Zero Tracker. https://zerotracker.net/, 2023 (accessed on November 14, 2023).

[2] Statistical bulletin of the People’s Republic of China on national economic and social development for 2022.

http://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/zxfb/202302/t20230228_1919011.html, 2023 (accessed on February 28, 2023).

[3] Global Energy Review: CO2 Emissions in 2021.

https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/global-energy-review-co2-emissions-in-2021, 2022 (accessed on August 3, 2022).

[4] Liu W., Wan Y.M., Xiong Y.L., et al., Outlook of low carbon and clean hydrogen in China under the goal of “carbon peak and neutrality”. Energy Storage Science and Technology, 2022, 11(2): 635–642.

[5] Wu P., Ma Y., Gao C., et al., A review of research and development of supercritical carbon dioxide Brayton cycle technology in nuclear engineering applications. Nuclear Engineering and Design, 2020, 368: 110767.

[6] Dostal V., Hejzlar P., Driscoll M.J., High-performance supercritical carbon dioxide cycle for next-generation nuclear reactors. Nuclear Technology, 2006, 154(3): 265–282.

[7] Dostal V., Hejzlar P., Driscoll M.J., The supercritical carbon dioxide power cycle: comparison to other advanced power cycles. Nuclear Technology, 2006, 154(3): 283–301.

[8] Ishiyama S., Muto Y., Kato Y., et al., Study of steam, helium and supercritical CO2 turbine power generations in prototype fusion power reactor. Progress in Nuclear Energy, 2008, 50(2–6): 325–332.

[9] Li Z., Shi M., Shao Y., et al., Supercritical CO2 cycles for nuclear-powered marine propulsion: preliminary conceptual design and off-design performance assessment. Journal of Thermal Science, 2024, 33(1): 328–347.

[10] Yang J., Yang Z., Duan Y.Y., Design optimization and operating performance of S-CO2 Brayton cycle under fluctuating ambient temperature and diverse power demand scenarios. Journal of Thermal Science, 2024, 33(1): 190–206.

[11] Wang K., He Y.L., Zhu H.H., Integration between supercritical CO2 Brayton cycles and molten salt solar power towers: a review and a comprehensive comparison of different cycle layouts. Applied Energy, 2017, 195(1): 819–836.

[12] Liu Q., Shang L., Duan Y.Y., Performance analyses of a hybrid geothermal-fossil power generation system using low-enthalpy geothermal resources. Applied Energy, 2016, 162: 149–162.

[13] Xu J., Sun E., Li M., et al., Key issues and solution strategies for supercritical carbon dioxide coal fired power plant. Energy, 2018, 157: 227–246.

[14] Sharma O.P., Kaushik S.C., Manjunath K., Thermodynamic analysis and optimization of a supercritical CO2 regenerative recompression Brayton cycle coupled with a marine gas turbine for shipboard waste heat recovery. Thermal Science and Engineering Progress, 2017, 3: 62–74.

[15] Moroz L., Burlaka M., Rudenko O., Study of a supercritical CO2 power cycle application in a cogeneration power plant. Supercritical CO2 Power Cycle Symposium, Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, USA, 2014.

[16] Li H., Jin Z., Yang Y., et al., Preliminary conceptual design and performance assessment of combined heat and power systems based on the supercritical carbon dioxide power plant. Energy Conversion and Management, 2019, 199: 111939.

[17] Yang Y., Wang Z., Ma Q., et al., Thermodynamic and exergoeconomic analysis of a supercritical CO2 cycle integrated with a LiBr-H2O absorption heat pump for combined heat and power generation. Applied Science, 2020, 10(1): 323.

[18] Wang J., Zhao P., Niu X., et al., Parametric analysis of a new combined cooling, heating and power system with transcritical CO2 driven by solar energy. Applied Energy, 2012, 94: 58–64.

[19] Fan G., Li H., Du Y., et al., Preliminary conceptual design and thermo-economic analysis of a combined cooling, heating and power system based on supercritical carbon dioxide cycle. Energy, 2020, 203: 117842.

[20] Zhang F., Liao G.L., E J.Q., et al., Thermodynamic and exergoeconomic analysis of a novel CO2 based combined cooling, heating and power system. Energy Conversion and Management, 2020, 222: 113251.

[21] Yang Y., Huang Y., Jiang P., et al., Multi-objective optimization of combined cooling, heating, and power systems with supercritical CO2 recompression Brayton cycle. Applied Energy, 2020, 271: 115189.

[22] Hou S., Zhang F., Yu L., et al., Optimization of a combined cooling, heating and power system using CO2 as main working fluid driven by gas turbine waste heat. Energy Conversion and Management, 2018, 178: 235–249.

[23] Angelino G., Carbon dioxide condensation cycles for power production. Journal of Engineering for Power-Transactions of ASME, 1968, 90: 287–295.

[24] Halimi B., Suh K.Y., Computational analysis of supercritical CO2 Brayton cycle power conversion system for fusion reactor. Energy Conversion and Management, 2012, 63: 38–43.

[25] Al-Sulaiman F.A., Atif M., Performance comparison of different supercritical carbon dioxide Brayton cycles integrated with a solar power tower. Energy, 2015, 82: 61–71.

[26] Zeyghami M., Khalili F., Performance improvement of dry cooled advanced concentrating solar power plants using daytime radiative cooling. Energy Conversion and Management, 2015, 106: 10–20.

[27] Coco-Enriquez L., Munoz-Anton J., Martinez-Val J.M., Integration between direct steam generation in linear solar collectors and supercritical carbon dioxide Brayton power cycles. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2015, 40: 15284–15300.

[28] Ma Y.G., Liu M., Yan J.J., et al., Thermodynamic study of main compression intercooling effects on supercritical CO2 recompression Brayton cycle. Energy, 2017, 140: 746–756.

[29] Ahn Y., Bae S.J., Kim M., et al., Review of supercritical CO2 power cycle technology and current status of research and development. Nuclear Engineering and Technology, 2015, 47: 647–661.

[30] Cheang V.T., Hedderwick R.A., McGregor C., Benchmarking supercritical carbon dioxide cycles against steam Rankine cycles for Concentrated Solar Power. Solar Energy, 2015, 113: 199–211.

[31] Liu Y.P., Wang Y., Huang D.G., Supercritical CO2 Brayton cycle: A state-of-the-art review. Energy, 2019, 189: 115900.

[32] Costante M.I., Prospects of mixtures as working fluids in real-gas Brayton cycles. Energies, 2017, 10(10): 1649.

[33] Costante M.I., Gioele D.M., An overview of real gas Brayton power cycles: working fluids selection and thermodynamic implications. Energies, 2023, 16(10): 3989.

[34] Du G.S., Liang G.L., Special gas storage and transportation, application, safety and characteristics-CF4, CHF3, C2F6, C3F8, F3N. Low Temperature and Specialty Gases, 1994, 1: 62–67 (in Chinese).

[35] Perez J.A., Evaluation of ethane as a power conversion system working fluid for fast reactors. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Massachusetts, USA, 2008.

[36] Sarkar J., Thermodynamic analyses and optimization of a recompression N2O Brayton power cycle. Energy, 2010, 35(8): 3422–3428.

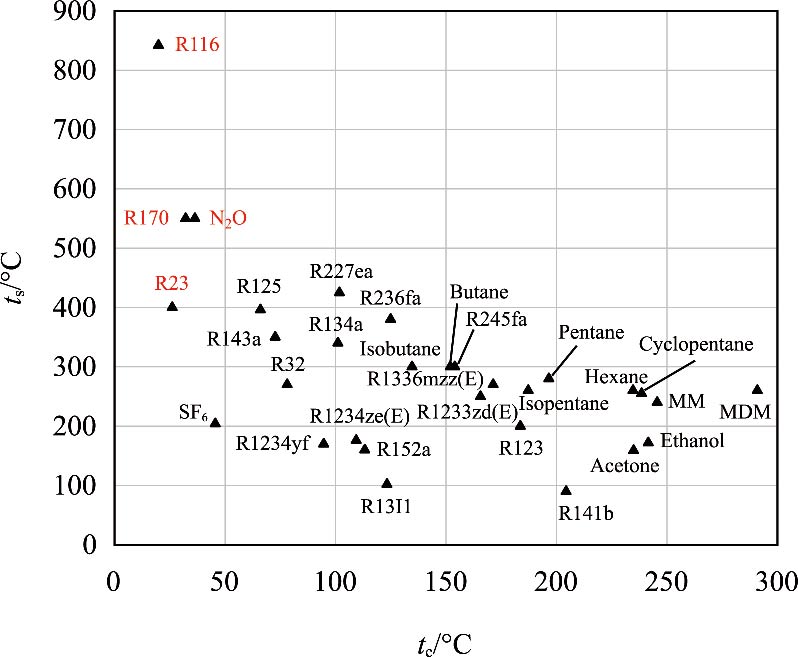

[37] Calderazzi L., di Paliano P.C., Thermal stability of R-134a, R-141b, R-13I1, R-7146, R-125 associated with stainless steel as a containing material. International Journal of Refrigeration, 1997, 20(6): 381–389.

[38] Dai X., Shi L., An Q., et al., Thermal stability of some hydrofluorocarbons as supercritical ORCs working fluids. Applied Thermal Engineering, 2018, 128: 1095–1101.

[39] Irriyanto M.Z., Lim H.S., Choi B.S., et al., Thermal stability study of HFO-1234ze (E) for supercritical organic Rankine cycle: Chemical kinetic model approach through decomposition experiments. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, 2020, 90: 244–250.

[40] Dai X., Shi L., An Q., et al., Screening of hydrocarbons as supercritical ORCs working fluids by thermal stability. Energy Conversion and Management, 2016, 126: 632–637.

[41] Wang H.X., Liu J.Y., Ren L.Y., Thermal stability measurement and selection of working fluids for the organic Rankine cycle. Journal of Tianjin University (Science and Technology), 2021, 54(6): 585–592 (in Chinese).

[42] Keulen L., Gallarini S., Landolina C., et al., Thermal stability of hexamethyldisiloxane and octamethyltrisiloxane. Energy, 2018, 165: 868–876.

[43] Xin L., Liu C., Tan L., et al., Thermal stability and pyrolysis products of HFO-1234yf as an environment-friendly working fluid for Organic Rankine Cycle. Energy, 2021, 228: 120564.

[44] Xin L., Liu J., Liu C., et al., Insight into the pyrolysis of R32 and R32/CO2 as working fluid for organic Rankine cycle. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis, 2022, 167: 105672.

[45] Angelino G., Invernizzi C., Experimental investigation on the thermal stability of some new zero ODP refrigerants. International Journal of Refrigeration, 2003, 26(1): 51–58.

[46] Xin L., Liu J., Liu C., et al., Experimental and Theoretical Studies on Thermal Stability and Pyrolysis Mechanism of R1233zd(E). Journal of Engineering Thermophysics, 2023, 44(5): 1169–1176. (in Chinese)

[47] Huo E., Liu C., Xin L., et al., Thermal stability and decomposition mechanism of HFO-1336mzz(Z) as an environmental friendly working fluid: experimental and theoretical study. International Journal of Energy Research, 2019, 43(9): 4630–4643.

[48] Mondal S., De S., CO2 based power cycle with multi-stage compression and intercooling for low temperature waste heat recovery. Energy, 2015, 90: 1132–1143.

[49] Zhou K., Wang J., Xia J., et al., Design and performance analysis of a supercritical CO2 radial inflow turbine. Applied Thermal Engineering, 2020, 167: 114757.