[1] Dagaut P., Cathonnet M., Boetiner J.C., et al., Kinetic modeling of propane oxidation. Combustion Science and Technology, 1987, 56(1–3): 23–63.

[2] Lam K.Y., Hong Z., Davidson D.F., et al., Shock tube ignition delay time measurements in propane/O2/argon mixtures at near-constant-volume conditions. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute, 2011, 33(1): 251–258.

[3] Penyazkov O.G., Ragotner K.A., Dean A.J., et al., Autoignition of propane-air mixtures behind reflected shock waves. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute, 2005, 30(2): 1941–1947.

[4] Cadman P., Thomas G.O., Butler P., The auto-ignition of propane at intermediate temperatures and high pressures. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, 2000, 2(23): 5411–5419.

[5] Herzler J., Jerig L., Roth P., Shock-tube study of the ignition of propane at intermediate temperatures and high pressures. Combustion Science and Technology, 2004, 176(10): 1627–1637.

[6] Gallagher S.M., Curran H.J., Metcalfe W.K., et al., A rapid compression machine study of the oxidation of propane in the negative temperature coefficient regime. Combustion and Flame, 2008, 153(1): 316–333.

[7] Cathonnet M., Boettner J.C., James H., Experimental study and numerical modeling of high temperature oxidation of propane and n-butane. Symposium (International) on Combustion, 1981, 18(1): 903–913.

[8] Hashemi H., Christensen J.M., Harding L.B., et al., High-pressure oxidation of propane. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute, 2019, 37(1): 461–468.

[9] Zhu L., Panigrahy S., Elliott S.N., et al., A wide range experimental study and further development of a kinetic model describing propane oxidation. Combustion and Flame, 2023, 248: 112562.

[10] Cord M., Husson B., Lizardo Huerta J.C., et al., Study of the low temperature oxidation of propane. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 2012, 116(50): 12214–12228.

[11] Koert D.N., Miller D.L., Cernansky N.P., Experimental studies of propane oxidation through the negative temperature coefficient region at 10 and 15 atmospheres. Combustion and Flame, 1994, 96(1): 34–49.

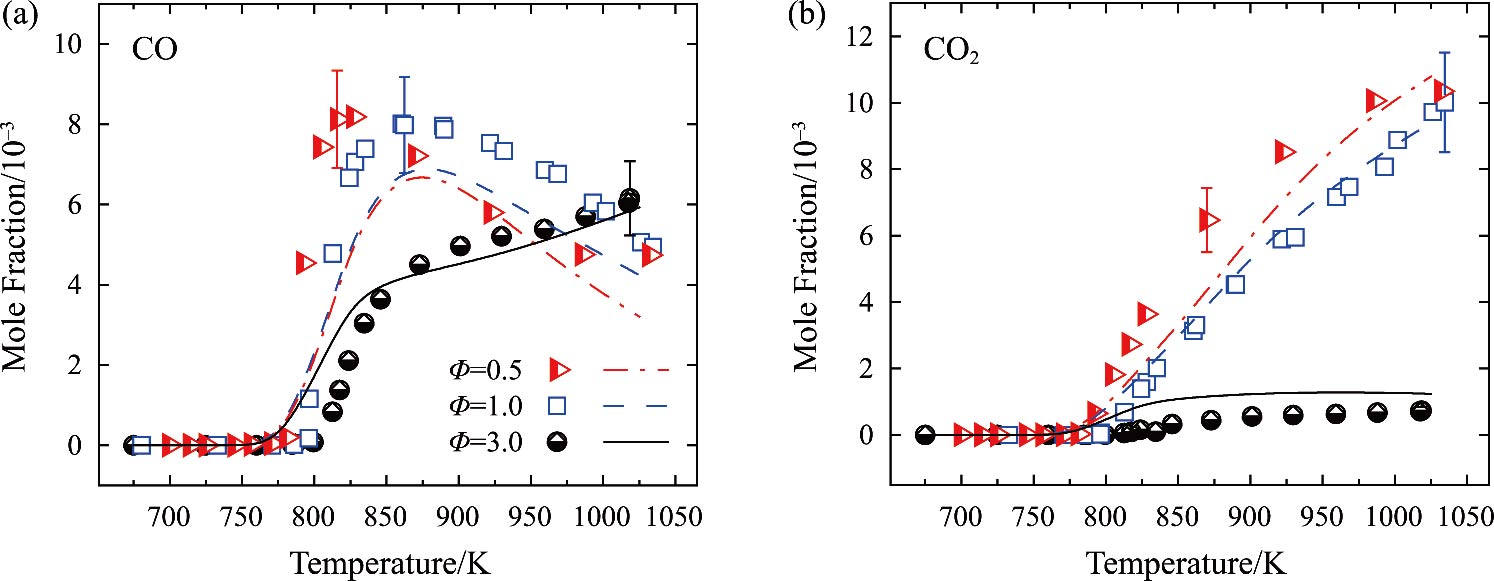

[12] Zhao H., Yan C., Song G., et al., Studies of low and intermediate temperature oxidation of propane up to 100 atm in a supercritical-pressure jet-stirred reactor. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute, 2022, 39: 2715–2723.

[13] Akram M., Kishore V.R., Kumar S., Laminar burning velocity of propane/CO2/N2-air mixtures at elevated temperatures. Energy & Fuels, 2012, 26(9): 5509–5518.

[14] Huzayyin A.S., Moneib H.A., Shehatta M.S., et al., Laminar burning velocity and explosion index of LPG-air and propane-air mixtures. Fuel, 2008, 87(1): 39–57.

[15] Razus D., Brinzea V., Mitu M., et al., Burning velocity of liquefied petroleum gas (LPG)-air mixtures in the presence of exhaust gas. Energy & Fuels, 2010, 24(3): 1487–1494.

[16] Tian Z.Y., Tian D.X., Chen J.T., et al., Experimental and modeling study on C2H2 oxidation and aromatics formation at 1.2 MPa. Journal of Thermal Science, 2022, 32: 866–880.

[17] Szulejko J.E., Kim K.H., Re-evaluation of effective carbon number (ECN) approach to predict response factors of “compounds lacking authentic standards or surrogates” (CLASS) by thermal desorption analysis with GC-MS. Analytica Chimica Acta, 2014, 851: 14–22.

[18] Laumer J.-Y. de S., Leocata S., Tissot E., et al., Prediction of response factors for gas chromatography with flame ionization detection: Algorithm improvement, extension to silylated compounds, and application to the quantification of metabolites. Journal of Separation Science, 2015, 38(18): 3209–3217.

[19] Tian Z.Y., Wen M., Jia J.Y., et al., Revisit to the oxidation of CH4 at elevated pressure. Combustion and Flame, 2022, 245: 112377.

[20] Zhou C.W., Li Y., Burke U., et al., An experimental and chemical kinetic modeling study of 1,3-butadiene combustion: Ignition delay time and laminar flame speed measurements. Combustion and Flame, 2018, 197: 423–438.

[21] Kee R.J., Rupley F.M., Miller J.A., CHEMKIN-II: A Fortran chemical kinetics package for the analysis of gas-phase chemical kinetics. Sandia National Lab. (SNL-CA), Livermore, CA (United States), 1989.

[22] Yuan W., Li Y., Dagaut P., et al., Investigation on the pyrolysis and oxidation of toluene over a wide range conditions. I. Flow reactor pyrolysis and jet stirred reactor oxidation. Combustion and Flame, 2015, 162(1): 3–21.

[23] Metcalfe W.K., Burke S.M., Ahmed S.S., Curran H.J., A hierarchical and comparative kinetic modeling study of C1-C2 hydrocarbon and oxygenated fuels. International Journal of Chemical Kinetics, 2013, 45(10): 638–675.

[24] Wang H., You X., Joshi A.V., et al., USC mech version II. High-temperature combustion reaction model of H2/CO/C1-C4 compounds.

http://ignis. usc. edu/USC_Mech_II. htm.

[25] Klippenstein S.J., Sivaramakrishnan R., Burke U., et al., HȮ2+HȮ2: High level theory and the role of singlet channels. Combustion and Flame, 2022, 243: 111975.

[26] Saxena P., Williams F.A., Testing a small detailed chemical-kinetic mechanism for the combustion of hydrogen and carbon monoxide. Combustion and Flame, 2006, 145(1): 316–323.

[27] Su G.Y., Tian D.X., Xu Y.F., et al., Oxidation study of small hydrocarbons at elevated pressure. Part I: Neat 1,3-butadiene. Combustion and Flame, 2023, 253: 112756.

[28] Dirrenberger P., Le Gall H., Bounaceur R., et al., Measurements of laminar flame velocity for components of natural gas. Energy & Fuels, 2011, 25(9): 3875–3884.

[29] Hu E., Jiang X., Huang Z., et al., Experimental and kinetic studies on ignition delay times of dimethyl ether/n-butane/O2/Ar mixtures. Energy & Fuels, 2013, 27(1): 530–536.

[30] Law C.K., Kwon O.C., Effects of hydrocarbon substitution on atmospheric hydrogen-air flame propagation. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2004, 29(8): 867–879.

[31] Egolfopoulos F.N., Zhu D.L., Law C.K., Experimental and numerical determination of laminar flame speeds: Mixtures of C2-hydrocarbons with oxygen and nitrogen. Symposium (International) on Combustion, 1991, 23(1): 471–478.

[32] Goswami M., Bastiaans R.J.M., de Goey L.P.H., et al., Experimental and modelling study of the effect of elevated pressure on ethane and propane flames. Fuel, 2016, 166: 410–418.

[33] Lowry W., Vries J.D., Krejci M., et al., Laminar flame speed measurements and modeling of pure alkanes and alkane blends at elevated pressures. Journal of Engineering for Gas Turbines and Power, 2011, 133(9): 091501.

[34] Jomaas G., Zheng X.L., Zhu D.L., et al., Experimental determination of counterflow ignition temperatures and laminar flame speeds of C2–C3 hydrocarbons at atmospheric and elevated pressures. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute, 2005, 30(1): 193–200.

[35] Seetula J.A., Slagle I.R., Kinetics and thermochemistry of the R+HBr⇄RH+Br (R=n-C3H7, isoC3H7, n-C4H9, isoC4H9, sec-C4H9 or tert-C4H9) equilibrium. Journal of the Chemical Society, Faraday Transactions, 1997, 93(9): 1709–1719.